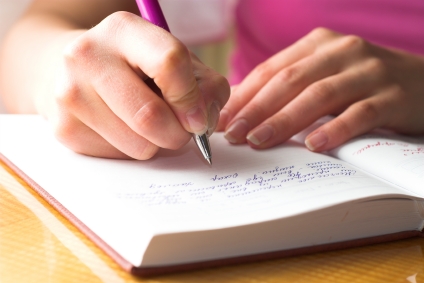

I suspect that note-taking – the simple act of writing down and elaborating upon key points from what we experience – is one of the most under-appreciated and under-utilized practices of effective lifelong learning.

I don’t have hard research to support this suspicion, but I know that I have looked around the room many times at conference sessions over the years and seen next to no one taking notes. (Admittedly, I take the somewhat cynical view that the people tapping away on their phones are more like doing e-mail or social media than using a note taking app.)

My hunch is that this situation has gotten worse as most conferences and formal educational experiences have migrated online. Sitting in a room with a presenter or facilitator a good distance away helps provide a sense of mental and physical space, an opportunity for the objectivity and reflection that contribute to good notetaking. With a digital presentation two feet in front of your nose and the constant distraction of chat that characterizes so many online events, the impulse to take notes may be effectively quashed.

And those are just typical live, formal learning experiences.

Again, experience suggests that it the rare person who applies the note-taking discipline of the classroom to the less formal, yet often more vital, learning experiences she encounters informally as part of day-to-day life. By that I mean not just obvious experiences like reading books or watching videos but all the myriad opportunities we have for learning.

If we want to remember; if we want to apply; if we want learning experiences to lead to actual positive change in our lives, then taking notes effectively is an essential practice.

Let’s take a closer look at both why and how.

Why Note-Taking Matters

The most fundamental reason note-taking matters is that we forget. Quickly.

Even if you don’t completely buy into Ebbinghaus’s famous forgetting curve, you probably know from personal experience that within a few days – much less a few weeks or months – you forget the vast majority of what you have seen or heard in your daily life.

So, notes are a way to aid memory, to make it possible to access what our brains may not be able to recall.

That’s certainly useful, but it’s also a step toward not having to rely on our notes to remember. A significant body of research supports the idea that simply writing something down contributes greatly to the process of moving it into long-term memory. As Françoise Boch and Annie Piolat note in their helpful overview of research on note-taking (upload to M2L)

the result of taking notes is much more than the production of a passive “external” information store, as the note taking action itself is part of the memorization process and results in the creation of a form of “internal” storage. (Kiewra, 1987) Furthermore, the taking of notes seems to ease the load on the working memory and thereby helps people resolve complex problems.

These results apply when taking notes from lectures (for example, Kiewra, 2002) – and there’s not a lot of reason to think it matters whether the lecture is live or digital. They also apply to taking notes from reading (for example, Rahmani & Sadeghi, 2011; Chang & Ku, 2014).

The likely reason that taking notes works is that it requires the note taker to make at least a modest level of effort rather than just passively absorbing the experience. While information can be written down in a purely rote, “copycat” manner, in most instances we’ll make at least some effort to understand what we are writing down as we distill it into shorter form. In the best instances, we’ll “elaborate” on what we are hearing or reading by, for example, connecting it to our own prior experiences and knowledge of jotting down questions about it.

Of course, doing all of this – and achieving the desired results from note-taking – requires an understanding of how to take notes effectively.

Keys to Effective Note Taking

Even those of us who are in the practice of taking notes often don’t do it well, particularly if (as is the case in most adult learning) we don’t expect to be tested.

In the first place, we may fall back on the common substitutes for note-taking: highlighting and underlining. But we know that these – along with their good friend re-reading – are simply not very effective as strategies for retention and learning. (Again, the level of effort required – or, in this case, not required – is probably a key reason.)

Even if you do write things down, though, that initial act is only part of the equation if you want to leverage the full power of note-taking. For full effectiveness, notes need to be:

- organized so that they can easily be accessed and reviewed

- reviewed multiple times over time

- re-worked and re-stated in your own language

- reflected upon

- connected to your existing knowledge

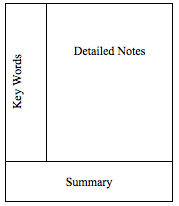

There are a number of approaches to capturing and organizing notes effectively, but one that has been broadly adopted is the Cornell method. The basic approach is to divide a page into three sections:

- a column on the right of the page for taking detailed (though concise) notes;

- a narrower column to the left for recording key words and phrases as you review the more in-depth notes you have recorded in the right column;

- a column across the bottom for writing a brief summary – usually a sentence or two – of the major ideas captured on the page.

The Cornell method is designed to support the five-step process above: organize, review, re-state, reflect, and connect. While originally developed as a method for taking notes during college lectures, it works well for most situations in which you need to capture and process information effectively.

If you are taking notes on paper, using the Cornell method is as simple as drawing a few boxes on the page, but there are also are plenty of digital Cornell method templates available for Word, Google Docs, and popular note-taking apps like Evernote, so making it a part of your life is pretty easy no matter how you take notes.

As you use the Cornell method or any other approach to taking notes, keep in mind that adding drawings to your notes may increase their effectiveness. (Wammes, Meade, & Fernandes, 2016) Don’t worry: Doing this doesn’t require any significant artistic ability. Simple stick figures or line drawings, arrows and circles used to connect key concepts, or basic Venn diagrams can be enough.

Also, while the quality of your notes should come first, the quantity of notes may also matter. (Nye, Crooks, Powley, & Tripp, 1984) As a rule, make sure you push yourself enough to be sure you have fully captured everything from the experience that may be relevant to your learning.

Is Note-Taking by Hand Better?

Possibly you’ve heard of studies suggesting that taking notes by hand – as opposed to on a computer or other digital devices – is more effective. My view is that the jury is still out on this question.

The main source of the “handwritten notes are better” meme is provocatively titled 2014 article in Psychological Science by Pam Mueller and Daniel. The article discusses a study conducted by Mueller and Oppenheimer in which three groups of students viewed TED talks and took notes either by hand or using a laptop. Even with the usual multitasking distractions removed – and with two of the groups of students being coached or trained on how to take notes well – the study found that “students who took notes on laptops performed worse on conceptual questions than students who took notes longhand.” Notably, the gap between the groups was attributed to “laptop note takers’ tendency to transcribe lectures verbatim rather than processing information and reframing it in their own words.”

So far, so good.

But a 2019 study that replicated the Mueller and Oppenheimer study and and extended it to include two additional groups – one that did not take notes at all – found “performance did not consistently differ between any groups” and any “differences were further decreased after students studied their notes.”

Additionally, a 2022 meta-analysis of research on note-taking found that there was “no effect of method (i.e., longhand vs. digital) on performance under controlled conditions.” Rather, this group of researchers suggested that the likelihood of distraction – e.g., multitasking – when working on a computer or other digital device might have been the underlying reason for earlier findings suggesting handwritten notes are better.

My main takeaway at this point is don’t worry about how you take notes, just make sure you do take notes.

Taking Notes Is Just Step One

Finally, while I’ve already suggested this above, it bears repeating that notes are not something to simply jot down and file away; they are to be returned to and actively mined over time if they are to really serve their purpose

I’ve written often about reflection as a learning practice on Mission to Learn. Notes can and should be a valuable part of this practice.

Make it a habit to return to and review notes you have captured in the past. Much better: challenge yourself to see how much you can remember from the notes before you actually re-read them. Write down what you remember and then re-read the notes. Then, consider taking notes on the gaps between your memory and what the notes say. Consider revising and rewriting the notes. This may even be a practice you want to incorporate into a journaling practice.

The bottom line is that note-taking – like learning itself – is not a one-time event; it is a process.

So, I encourage take some time to examine your own note-taking practices, work on improvements, and make effective note-taking an essential part of your own mission to learn.

Pingback: This Note-Taking Life | Loose Leaf Writing

Pingback: Words on a page » Blog Archive » A few links for the end of the week - A blog about writing, in its various forms

Pingback: Middle School Matters » Blog Archive » MSM 171 TwittervISTE #ISTE11

Note-taking is also key for many creative tasks (and arguably creative tasks are a kind of learning–think of Frost’s “no surprise for the writer, no surprise for the reader,” and what is surprise but a discovery, learning something new?). I’m thinking of writing, especially poetry. I honestly think that 100 percent of the poets I know writing today keep a notebook with little phrases and observations. They go back to that notebook over time, and often images and words from years ago finally find a place in a poem. All the more reason to do the kind of review of notes that you’re suggesting, Jeff.